Myanmar's 20-year-old mini-grids: what can they teach us?

Every night as the sun sets over his village in Southeast Myanmar, Aung Moe Win switches on his 30 kW generator. Its low rumble seeps into all the kitchens, sitting rooms, and bedrooms of the village’s 290 households. But the noise quickly gets drowned out by children cheering, news anchors reporting the day’s headlines and Burmese covers of 80’s pop songs.

It is almost 20 years ago now that Aung Moe Win visited a nearby village and saw them using a diesel generator to produce electricity. Back then, the only night-time lighting available in his village came from candles and kerosene lamps, which cost his neighbours almost 20% of their monthly income. Determined to change this, Aung Moe Win gathered the necessary funds – mostly his own savings plus some small donations from the villagers – and proceeded to install a generator, set up distribution lines, and connect the village’s households, all without any formal training.

Aung Moe Win proudly showing off his generator as he gives us a tour of the mini-grid. Every night at 6 PM, he turns it on with the crank of a wrench, providing basic but necessary lighting and charging to his community.

The building that houses Aung Moe Win’s generator and the initial set of distribution poles that go to the households in the village.

Commitment in the face of constraints

Aung Moe Win’s is one of an incredible 13,000+ villages in Myanmar where rural electricians – called “meesayar” – drew on what limited financial and knowledge resources they could gather to provide electricity to their communities. The practice is known locally as “ko-htu-ko-hta mee-lin-yae”, roughly “self-help electrification”. Their systems take on many different shapes and sizes, varying in households served, tariffs, and operational structures. And in that diversity lies one of their main strengths. We have met with meesayar who have developed tailored payment schemes correlating with seasonal incomes from harvest cycles, some who will trade electricity for produce, and still others who have built cooperative structures for operating and maintaining their grids. These mini-grids, and the governance systems that care for them, are built to fit the resources, constraints, and needs of their villages. That is how, even in the face of severe resource constraints, they have grown to currently serve 12% of Myanmar's off-grid population.

We have found and learnt from meesayar by looking for distribution poles made of collected tree trunks and bamboo poles along the street, signs of a local mini-grid.

Still, there are important challenges related to the reliability, cost, and environmental impact of these systems. The mini-grids typically run for only 3-4 hours a day. They generate electricity at on average US$0.65/kWh, far above the US$0.02-0.06/kWh paid for grid electricity in Myanmar. And they run on costly and polluting diesel fuel. However, 100+ personal interviews with meesayar and the households they serve have shown us that communities want to improve their mini-grids (understanding that the government is unable to help them). They simply need help accessing the money and skills they require to be able to do so.

Old mini-grids, new opportunities

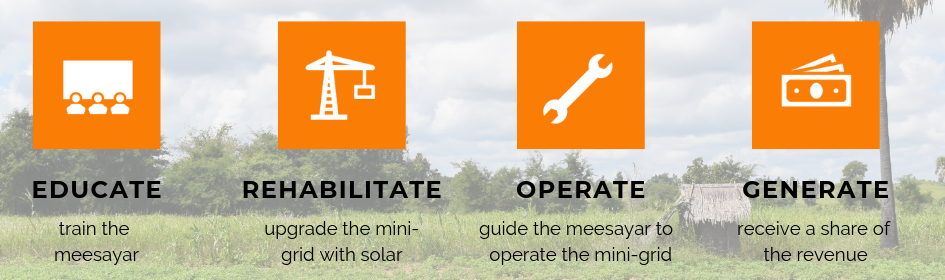

Mee Panyar addresses both these issues using the existing mini-grids as our foundation. Rather than start from scratch, we believe that we can achieve more, and have lasting impact by building on what communities have already built themselves. Through a hands-on training program run in the village, we teach the meesayar proper operation and maintenance practices so that their systems can provide electricity more reliably. We also teach them how to hybridise their mini-grids with solar and provide the necessary funds. In doing so, we can decrease household electricity prices by up to 50%, increase operator profit 3x over, and reduce carbon emissions by 60%. After enabling the meesayar to upgrade and de-carbonize their mini-grid, we receive a portion of their increased revenues. This way we can recover our investment, which allows us to reach more people and more mini-grids.

Our project model in each village ensures that the meesayar can more effectively provide electricity to their village and Mee Panyar can recover our costs and invest in more villages.

On a wider scale, our work will build a qualified workforce of rural electricians. In Myanmar alone, roughly 12 million people are expected to be electrified through solar mini-grids. Worldwide, more than 40% of the almost 1 billion people currently still without access to energy will be reached through off-grid solutions. Connecting these households, most of whom live in rural areas, and the sustainable development of the energy sector as a whole will require a huge number of skilled workers and entrepreneurs ready to operate and maintain these grids. Building off of Myanmar’s self-help practice, as we do, presents a unique opportunity to meet that need.

Myanmar is just the beginning

It also presents an opportunity to find solutions to some of the major challenges that have plagued energy access efforts for years: low and difficult to forecast rural demand for electricity, challenging and uncertain policy environments, and poor engagement with and understanding of difficult to reach last-mile communities. Myanmar’s villages have proven their ability to find creative and tailored solutions that overcome some aspects of these issues. In general, we believe that communities are themselves best suited to determine what they need, and, if provided with the appropriate resources, can create and sustain it. There are plenty of examples of this also beyond Myanmar, from electricity-free refrigeration using clay pots, to relying on ‘‘missed calls’’ to communicate messages using prearranged protocols. In the face of constraints, communities commit.

Moreover, as communities take on these challenges, they create improved and secure livelihoods. Off-grid energy has the potential to create more than 4.5 million jobs globally. Effective community involvement in striving for SDG 7 – “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all” – can in that way be a major contributor for meeting SDG 8 – “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”. Communities can and have to be seen as an active part of the solution.

At Mee Panyar, we want to take community participation a step further by building every aspect of the mini-grid value chain in partnership with the community, and returning the decision-making power to their hands. Together with our partner, Aung Moe Win, and his village, we are piloting this model and beginning to transition Myanmar from one of the least electrified countries in the world to an example for community-driven energy development and livelihood creation.